Freeing up systems, 2021

Camille Chenais

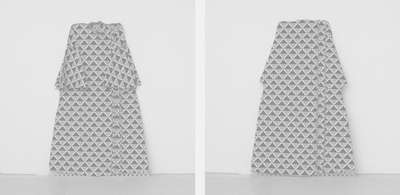

As I arrive one morning at the Maison du Danemark in Paris, I see a man hoisting two huge red flags with a white cross — Denmark’s official symbol. I’m told that the flags are raised every morning and taken down every evening. Stepping back outside, I watch them billow in the breeze. A flag is a sign of recognition. Its simple, clearly defined forms and vivid colours convey an identity that is meant to be unchanging and timeless. A flag stands for a nation or community. While it creates a sense of belonging, it can also make people who aren’t part of the community feel excluded. In the exhibition area, we come upon large fabric works that replicate the configuration (a hummingbird’s tail) and size of the Danish flags fluttering in front of the building. But in this case, the large expanses of fabric punctuate space, creating complex, undulating forms. These Flags of Freedom are collages of cutouts ranging from plain to variegated to patterned fabrics. It’s almost as if pieces of daily life — garments, tablecloths, curtains — were taking up their quarters on otherwise abstract flags, anchoring them in concrete reality. Rather than putting forward a stable, shared identity, the flags created by Mette Winckelmann seem to express shifting, organic, free-floating identities. Combining fabrics in various shapes, sizes and colours, these works show continuity with Scandinavian patchwork, traditionally a collective activity engaged in by women. The patterns and rhythms on the flags seem to tell more fluctuating, more fleeting stories than the straightforward signs and pure colours on national flags do. As Mette Winckelmann sees it, “Patchwork represents … an alternative to mathematical and logical thinking, as a system that is organically subject to the individual person’s body and hand.”1 As a result, Winckelmann can deconstruct and revamp the forms and categories of abstract and conceptual art, and organically transform the grid, a frequent motif in the works on display at the Maison du Danemark.

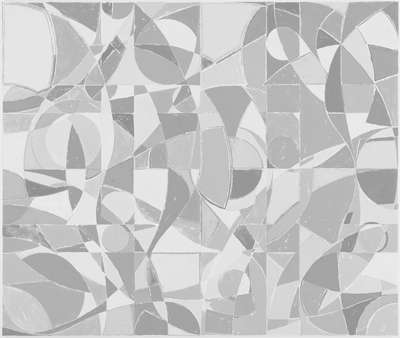

Art historian Rosalind Krauss has termed the grid “emblematic of the modernist ambition within the visual arts”. 2 Mette Winckelmann in turn claims to see clarity and coherence in it. 3 In her works, grids get bent, reshaped and blurred, yet without precluding structure and classification. They establish coordinates, mapping, arranging and dividing. They organize a territory, providing its warp and weft. They guide the viewer’s gaze. A grid can also be comforting, conveying the sense that you can fit in, find your place and feel safe in an established order. It emerges as a reflection of society’s underlying structure, rules and laws. But a grid isn’t stable. It sways and stumbles, highlighting its own flexible, unfinished character. A grid is potentially unlimited and non-centred, like a small fragment of a far larger whole. Winckelmann’s works that make use of grids seem to be without beginning or end; they have the potential for infinite rearrangement. As she explains, “I find it exciting to explore geometry and mathematics as systems that also reflect the structure of society. I like to take elements of those systems and nudge them towards something that is more open, organic and human. In a way, it’s a process that can also highlight a doubting, questioning attitude and the disintegration of the system.”4 Underlying the abstract quality of her works is a drive to liberate and dissolve art forms and categories that is rooted in an effort to rethink our own bodies. In the article “Mette Winckelmann — Patchwork as a Research Method”, Iris Müller-Westermann5 describes how the Danish artist works. She starts out by deciding on a method and rules that will dictate the way she places coloured forms on a backdrop. Her next move is to react to this system — often a grid — which she proceeds to break up, repurpose and distort. In doing so, Winckelmann underscores the power of systems while revealing the constraints and limitations they set for our lives, our bodies. The aim here is not to superimpose a grid-like structure on the world or to distinguish overriding concepts, but to use organic abstraction to explore the fluid, flexible nature of our personal, political and corporeal relations. As we step into the exhibition area, we are greeted with a fabric composed of four strictly delimited frames that contain the sentence “WE HAVE A BODY” — as if reminding us of the highly intimate physicality we all possess but tend to undervalue, particularly in abstract, conceptual art. The words on the flag thus form a counterpoint to the sense of order created by the work’s geometric layout. Winckelmann’s art is consistently conceived of in relation to the position of a human body, whether the artist’s or the observer’s. This view echoes the situated knowledges articulated by Donna Haraway: “I am arguing for the view from a body, always a complex, contradictory, structuring, and structured body, versus the view from above, from nowhere, from simplicity.”6

The grid also evokes textile weaving, a ubiquitous feature of Winckelmann’s work. This apparently abstract form reveals its full materiality when matched with the intertwining of weft (horizontal yarn) and warp (vertical yarn). Viewed in this light, a grid suddenly seems to be smiling wryly at us. Pompous and selfassured in works by Piet Mondrian or Sol Lewitt, grids as revisited by Winckelmann call to mind tea towels, garments and blankets, a world of fabrics traditionally considered “female”. When Anni Albers joined the Bauhaus in 1922, she was accepted into the weaving workshop, towards which the school systematically directed women artists. Even such a pioneering movement dedicated to breaking down the boundaries between art and life, between arts and crafts, upheld a sexist, gendered view of what activities were suitable for women. As a student at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, Winckelmann soon became aware of the hierarchy still in place, which held textile work in lower esteem than canvas painting. Weaving was equated with women’s chores, handicrafts and day-to-day household drudgery, whereas painting was considered a high-status form of expression because it had no functional value, but existed for its own sake. Like other artists before her, for example, Rosemarie Trockel with knitting and Hessie with embroidery, Winckelmann has reclaimed what was conventionally viewed as a purely feminine idiom to subvert it, offering a feminist counterhistory of abstraction.

On the exhibition area’s floor stand ceramic works that revive medieval forms. The title, Blood Phlegm and Bile, alludes to the humoural theory that formed the basis of medicine in Antiquity. At the time, the human body was thought to contain four humours — blood, yellow bile (choleric humour), black bile (melancholic humour) and phlegm — whose changing mixture affected our character and health. In La matrice de la race, Elsa Dorlin demonstrates how such medical discourse forged the vision that women’s bodies were intrinsically ill, thus justifying sexual inequality. The female body was seen as “a body prone to suffering, to the discharge of fluids and congestion, a body in agony”.7 In observing this array of phials, pitchers and jars on the floor, I begin to imagine them containing all those supposedly unhealthy fluids that were believed to make up women’s bodies. The glaze on the ceramic works almost seems to run, squirt and splatter, symbolizing that very surfeit of bodily fluids. Winckelmann provides an ironic take on the theory of four humours through the symbolic use of four glazes — red, white, yellow and black — to create random effects that only emerge after the works have been fired, and that undermine an allegedly rational attempt to understand the human body by encapsulating it in a system. Her works suggest that our bodies, gender, sexuality and social ties are fluid, elusive and flexible.

What first strikes the visitor on entering the exhibition area are the colours that seemingly dance across the works on display: bold at times, highly contrasting at others, subtly shaded and diaphanous to the point of transparency at still others. Like the forms in which they feature, these colours are anything but neutral. They convey a whole world of references, sensations and symbols. As the artist explained to Jérôme Sans: “Over the years, I’ve done research into the history of colour to try to grasp how individual and collective perceptions of colour have evolved over time. Colours are signs that we ‘read’ with our senses….”8 In 30,000,000 Lesbians (2009), red, yellow, white and black predominate. As colours that belong to the iconography of social and protest movements, they are assertive; they make a statement. Here, they bring to mind patterns on skirts worn by the artist’s mother or Asian fabrics and, for that reason, they give a surprisingly familiar quality to what might come across as a political banner. This work is a response to an official statement from the People’s Republic of China that there are no lesbians in the country, as well as to the overrepresentation of men in Western depictions of homosexuality — what Alice Coffin has termed “lesbian invisibility”.9 Based on the average percentage of lesbians in the global population, Winckelmann reckons that China may be home to some 30 million of them. As clearly demonstrated here, the political and social message in her art is embedded in the very materials, colours and forms she uses. It is inextricably bound up with the creative process itself. However, in contrast to the assertive, self-confident mental projections typical of abstract artists in the early twentieth century as they put forward a new vision of the world and art, Winckelmann’s works make no assertions — except that none can be made. With their fluttering, embodied lines, they hint rather at the fluid nature of our world and our ever-changing identities. Through the way she combines forms, colours and materials, Mette Winckelmann gives us a glimpse into her thinking, her creative processes and her doubts. Her work isn’t monolithic; it is diffuse, part of an ongoing, living process. We are dealing here with open works of art.

Camille Chenais is an art historian and exhibition curator with a focus on contemporary artistic practice. She lives and works in the city of Saint-Denis. She was in charge of exhibitions and residency programmes at Bétonsalon, Centre d’art et de recherche & Villa Vassilieff in Paris, from 2015 to 2021, where she served as curator for several exhibitions and assisted many artists with their research work.