Mette Winckelmann – Patchwork as a Research Method, 2013

Iris Müller-Westermann

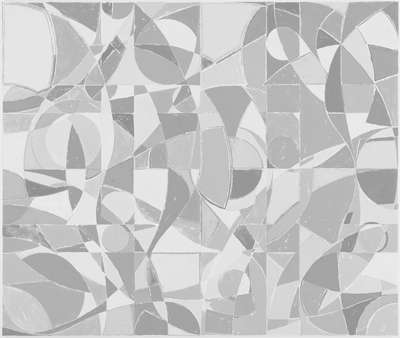

Mette Winckelmann’s large abstract paintings recall on first sight Danish concrete art of the 1950s, such as the constructive-abstract works by Richard Mortensen. On closer inspection, however, we discover that many of the artist’s works are not abstract paintings but are in fact collages of textiles. The pieces of fabric are sewn together like a patchwork on top of a base of canvas, other fabrics, or on wood.

Traditionally, patchwork is a handicraft in which fabric remnants of different shapes, sizes and colours are sewn together to make a larger picture of repeating patterns. In the past, this technique was often used for quilts, cushion covers, bags, tapestries, clothing and much more.

In many of her works, Mette Winckelmann combines textile collages with painting, as in The Turn of the Screw, 2013. A common characteristic of these works is the symmetry of their geometric structures.

Patchwork as a research method

For Mette Winckelmann, the technique of patchwork, has over the years, become a working method– a method that she used in the beginning to study her artistic sources and her role as an artist in a world founded on an art history created by men through the actions of men. In the course of time, patchwork has also become a strategy through which she visually organises and structures the world in her work, thereby researching it.

During our first conversation, Mette Winckelmann told how she – even before she could read and write – sat at a sewing machine and sewed pieces of material together, as was the tradition on the southern Danish island of Als where she comes from. The island’s women saved all their fabric remnants to later sew them together into rugs and quilts. The women around Mette Winckelmann used patterns that often carried a long tradition with them. In some instances, it was possible to see who had made the quilts by merely studying the patterns. A pattern was like a melody that could be picked up by another woman who could change it and develop it further.

When Mette Winckelmann began studying art at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen later in life, she soon realised that there existed a hierarchy within the art world. Work with textiles ranked lower in status than painting. Textile work was associated with handicrafts and womanhood, with women’s work and practicality; painting was a male form of expression that enjoyed greater status as it did not need to have any practical or useful function and existed only for its own sake.

Dealing with gender issues

Dealing with gender issues has become an important aspect in Mette Winckelmann’s work ever since. She began combining painting with textiles in order to study the validity of the existing hierarchy. By doing this she continued and carried on what artists like Rosemarie Trockel were engaged in since the 1980s. For example, we can think of Trockel’s large machine-knit wool pictures, ornamented with symbols of male power, and mounted on stretchers like paintings on canvas. Or we can think of the German artist’s white »minimalist paintings«, which, upon closer inspection, reveal themselves to be enamelled metal plates upon which, instead of black painted circles, black hotplates are mounted. In addition to the material wool and the element of handicrafts, the woman’s universe – the kitchen – was sneaked in to the art world by Trockel in a rebellious way, researching the ruling criteria. By doing this, she clearly brought to light the existing order of rank created by men.

Creating and transgressing systems

Mette Winckelmann’s works – both those that combine fabric and painting and those that are made of fabric alone, but also here pure paintings – come into being through a process comprising several phases. For each work, she first decides upon a system according to which the coloured forms are arranged on the base. For example, every second element could be grey and every third element yellow. All the following steps are decided upon after this first system is applied. In a next phase, she reacts to this outline based upon male rules by breaking these rules. Mette Winckelmann’s work does not merely deal with setting up systems, but it also deals with breaking down these systems and structures, thereby opening and going the self- imposed boundaries. Her works show that systems and structures are necessary, yet at the same time she draws attention to the fact that any system is also a limitation and a restriction that should be questioned. The balance between carrying out an instruction, which has a form of meditative character, and the questioning and transgressing of the system, is a central process within all of Mette Winckelmann’s work.

The fascination with the fact that combining pieces of fabric constantly creates something new and unexpected is a key force driving Mette Winckelmann in her work. Fabric is also a very flexible material; unlike oil paints, it can be worn close to the body, becoming like a second skin. And aside from clothing, curtains, flags and many other things can be made using fabric. Flags are a recurring feature in the works of Mette Winckelmann. Flags are symbols of identity, for ideas and concepts we have about ourselves and others. For Mette Winckelmann they represent an opportunity for self-reflection.

Whereas her earlier works consisted of elements of strong colours and were rather dense in character, her new works are more open, airy and transparent. Many of them are reminiscent of light which is broken by a prism, or stained-glass windows in a church. Here we can clearly see how she strives to transcend the inherent characteristics of the material and a spiritual space opens up. Some of these works exude light that appears to originate from within the material itself rather than from outside.

Extending the patchwork into the room

With her 2011 exhibition We Have a Body at Copenhagen’s »Den Frie Centre of Contemporary Art«, Mette Winckelmann took her study of patchwork as a method one step further. Here, she included the exhibition room itself in her work, creating a three-dimensional patchwork. By extending her work out into the room, she expanded the experience that we have as viewers when encountering her work. When visitors entered the room they experienced themselves as part of the three-dimensional structure. The visitor was no longer merely an onlooker but became part of the installation itself. This reminds me of Marcel Duchamp’s staging of the International Exhibition of Surrealism, in Paris in 1938 where he burst »The White Cube«, and instead of hanging works on white walls, he created an experimental space taking the visitors on a journey into the depths of the subconscious. In the spartanly lit rooms, in which simply moving around was made difficult and was at times decidedly frightening, visitors came face to face with unexpected objects, including the famous coal sacks hanging from the ceiling and many dream-like scenarios. With We Have a Body, Mette Winckelmann created an experimental space aimed at introducing her works not only to the intellects of the visitors but to all of their senses.

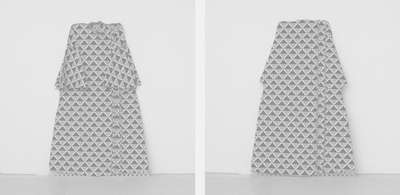

In her public outdoor installation Belief and Superstition at »Viborg Kunsthal«, Mette Winckelmann covered a wall separating the museum from the surrounding city environment with concrete pavers arranged as a patchwork, forming large scale patterns. These patterns are symbols found by the artist in museum collections of folk art, as well as in Scandinavian and American books and websites about patchwork. In total, 100 different symbols composed of 36 pavers each in five different nuances of grey and brown have been placed in three rows along the wall. These symbols have predominantly Christian roots and refer to beliefs and superstitions.

However, these symbols are not arranged according to content, faith or hierarchy – each is presented with equal status to its neighbour. Here, we find The Star of Bethlehem, The Children of Israel, Jacob’s Ladder, The Steps to the Altar, The Streets of Jericho, The Eye of God and many more. This work does not reflect a particular religious viewpoint, but rather shows, kaleidoscopically, the multi-faceted and nuanced ways in which humans through centuries with the Christian paradigm as a base have tried to understand the greater contexts of our existence, the world and our own role in it. Only the pattern in the middle row is presented in its entirety, whereas those in the upper and lower rows have been cropped, giving the impression that we can extend the panorama of patterns both upwards and downwards. In this work, Mette Winckelmann refers to the long religious history of the city of Viborg itself, which up until the middle of the 17th century was the largest town in Jutland. Already in pre-Christian times Viborg (whose name comes from »viberg« meaning Holy Mountain) was the most important centre of political and jurisdictional power in Jutland. Later, in the Middle Ages, Viborg with its 12 churches (including the famous cathedral) and six convents had also become an important Christian centre. In Viborg, many different monastic orders within the Catholic Church met, including Dominicans and Franciscans but also others. Later in the 16th century the town became an important centre of the Reformation. For Mette Winckelmann, the work Tro og Overtro is not about right or wrong ideas of faith but about creating a panorama of different perspectives that can offer inspiration to the viewers, perhaps causing them to think about their own ideas, insights and beliefs.

In the exhibition here at Brundlund Castle Art Museum, the patchwork principle has again been expanded and given a further dimension: the castle, which houses the exhibition galleries, is in itself a patchwork. Since its founding by Queen Margrete I in 1411, the castle has been rebuilt and extended many times to meet changing needs, and it mirrors in its present form kaleidoscopically its more than 600-year long history. In her exhibition here, Mette Winckelmann reacts to the castle’s architecture inside as well as outside, by creating a dialogue of her own works with the castle’s architectural patchwork. When I spoke with her, the exhibition was still in the planning stages, and Mette Winckelmann told me how curious she was to see what the architecture would do with her work and her work with the castle’s architecture.

Mette Winckelmann’s work here at Brundlund is not confined to the castle itself– she has also included the castle garden in her exhibition. Here, she has created a pattern of bricks that stem from an old, demolished Lutheran Mission House from the city of Haslev. Times have changed, and many of these so-called »missionshuse«, which were meeting places for religious congregations, have been demolished in more recent times, such as the Bethesda building in Haslev, which was built in 1905. The hard-fired bricks from the building’s façade, which previously formed an architectonical frame within which people practised the spreading of their faith and intentions through their words and actions, have now been spread out horizontally in the castle garden. There are exactly 602 bricks – one for each year since the castle was founded in 1411. One of the questions that the work brings to the fore is to what extent the energies embedded within the old bricks are transferred to their new surroundings and to those visiting the exhibition.

Perhaps we might sense the energy as a mood, as thoughts coming to our minds or in other ways.

Patchwork always includes a reaction to the work of others, as we can see here. While Mette Winckelmann in the past used to meticulously plan and control the artistic process, her works nowadays come into being more and more through dialogues. The materials she uses have their own will. Everything is constantly moving and changing. Mette Winckelmann’s work always embodies a balancing of contradictions, it deals with processes or as the artist herself puts it in perhaps what can be said to be her most important maxim: »A flexible form is the sublime – not the one sublime result.«