No Hierarchies, 2020

Kristina Stoltz

I meet with Mette and Laila in the backroom of Laila’s store. Mette has asked me over to discuss their planned collaboration. I’m familiar with Mette Winckelmann’s earlier work: colorful, system-based abstractions, often in fabric or in fabric on canvas. I have never heard of Laila Uti before. Her store turns out to be one of many on this strip of Copenhagen’s Nørrebrogade selling dresses and fabrics from the Middle East. On the gray facade, white sign letters spell out “LAILA UTI.” Two letters are conspicuously missing: the first and last letters of “butik,” the Danish word for store. This throws me off a bit, but I forget about it a moment later when I enter the store and a woman who must be Laila greets me and resolutely leads me through the tightly packed store and into a backroom that looks at least ten times bigger than the store itself.

The warehouse-like space has much higher ceilings than the front room and is divided by partitions of corrugated plastic and masonite. On these seemingly rickety dividers hang robes, shirts and gowns in colorful, patterned fabrics. It looks a mess, though I still get a sense of an underlying system. Laila takes my hand and pulls me through the rooms until we reach the end of the warehouse, where Mette is sitting behind a partition among piles of dressmaking fabrics. This is where we will be having our meeting. Laila unfolds a chair for me and one for herself and sits down next to Mette.

Mette tells me how they met in the intersection in front of the store. She was on her way in to look at some robes for an exhibition. Laila was headed the other way, but when she and Mette crossed paths, she turned around and followed her into the store.

I look at them. Both have long hair. Laila’s is black, Mette’s is blond. Mette is wearing a white shirt buttoned up. Laila is also wearing a shirt, a patterned one, with the top few buttons open. She tells me she wasn’t actually planning to return to the store the day she met Mette in the intersection.

“I was heading into the blue.”

It’s a cycle, Laila tells me. Life is like that. There are times when everything you have built up, or the person you have become, changes. You enter a new stage, and something new has to happen.

“But when I met Mette out in front, I realized I should remain Laila Uti a while longer.”

Mette and Laila laugh, and Mette moves her chair back to braid Laila’s hair. She needs Laila’s intuitive approach in her new works, she tells me. She hopes they can find a way to work together. Laila seems open to the idea. All it takes is getting started, she says. We get up to see more of the place – the partitions that seem to go on forever, the piled fabric, the folding chairs and folding tables, the espresso machine in the middle of everything, the smell of cinnamon and exhaust fumes, as if I had arrived in a new city. Laila disappears around a corner and Mette approaches me wearing beige, slightly oversized coveralls with the sleeves and legs rolled up. Taking my hand, she leads me through new divisions in the room. Strewn on the floor are tools and boxes of screws and nails, a power drill. She props up a canvas that she and Laila just painted together.

“It was quite unpleasant,” she says.

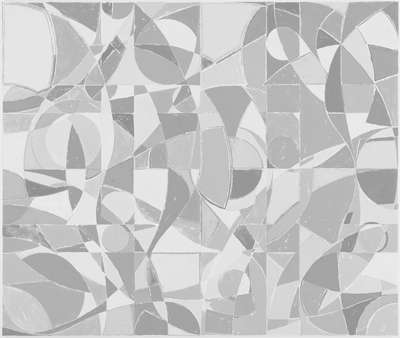

I look at the canvas, which is stretched with a length of black, gray and burgundy fabric and painted in silver and graphite-gray strokes. I ask why it was unpleasant and she tells me it was the lack of a system: no ruler, no calculations, just a loose hand, brush in pail, and go! Laila has no reservations, Mette tells me, she just paints.

“It’s like she takes over the whole space, like there’s no space left for me.”

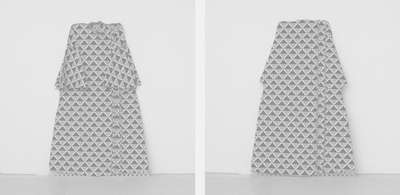

She gets out another canvas, and another, setting them side by side in front of me. They are stretched with lengths of fabric: silk, scarves, scraps of dresses and shirts from Laila’s store. The wooden stretcher and the nails holding the fabric are clearly visible. The fabric is painted over in patterns of black, white and metallic.

“By revealing the materials, the nails and the stretcher bars, and using metallic hues, we point to function over decoration. And we upend the hierarchy, putting the bottom at the top,” Mette says.

Laila has joined us, without my noticing. She is wearing matching beige coveralls, like Mette, with the sleeves and legs rolled up. Something about her seems changed, but I can’t put my finger on it, as if she had both come into sharper focus and lost her outline at the same time.

“We use a material,” she says, “fabric, which most people associate with weakness, because of its connotation to female craft. Then, when we use it in a way that’s anything but monolithic, things get challenging.”

She puts her arms around Mette. For a brief moment, it looks like Mette is disappearing into her, becoming her. My eyes blur, and I take a step back. Once again, they appear to me more or less sharp: two separate individuals. But only momentarily, before they again blur into one, like colors running together, materials mixing. Laila unfolds a chair and asks me to sit down.

“Getting dizzy in this situation is normal,” she says, stepping in front of Mette. “Your view of the artwork is being challenged. You have to understand that we are dealing with works here that screen each other, interrupt each other, blur each other out.”

Now Mette steps in front, so I can’t see Laila.

“We tear down and build up simultaneously,” Mette says, “or at least that’s what we’re trying to do. We want to challenge the monumental work of art by dispersing ourselves. We want to make a dispersed rather than a collected work.”

“A work where we are both inside and outside at once,” Laila says. I can hear her, but I can’t see her. I guess she has disappeared around the other side of the partition, but her voice seems to be coming from somewhere else, as if it were coming from inside of me.

“Inside and outside,” she continues. “The work will remain incomplete, yet you as a viewer still get a sense of structure.”

Mette props up several more canvases, side by side, one in front of the other, on the floor and in my lap. There seems to be an infinite number of them. She appears to have no problem taking over the space or going into the works: I see both her systematic, stringent line and Laila’s loose, soft hand. Laila who now calls to us. We place the canvases in a stack and go to the other side of the partition.

We enter the show. Laila Uti’s backroom and Mette Winckelmann’s studio. A stage set, the bones of every metropolis. A meeting of two individuals in the street, as that meeting looks from outside and inside, from above or below. The way things look when you step out your front door and meet the world with an open mind, relieved of gender, age and time. If that’s even possible. It is. For a brief moment, when you take a deep breath and exhale, as everything emerges anew. In that moment, there are no hierarchies. The cheap, synthetic fabrics from Uti’s store and the Christian Lacroix gold and effects on the over-painted canvases are equal, as they rest against the partitions. Likewise, the garments in Uti’s store, hand-sewn models in expensive furniture fabric or stout cotton versions with open stitching, are equal. Pinned up on flat mannequins, they are canvases.

I see Laila appear between corrugated plastic and masonite, wearing a patterned dress. I hear her voice, but I don’t catch what she is saying. I see her disappear into the crowd further down the warehouse, heading into the blue, into the next room where the show goes on, the city goes on, forming a new pattern, a new show, starting here and over again.