Printed Matters – On Mette Winckelmann’s painting installation Come Undone, 2016

Andreas Nilsson

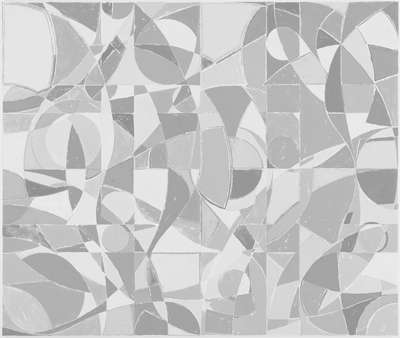

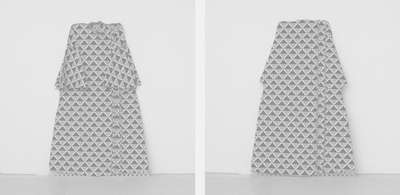

Several large-scale paintings loosely fixed to wooden frames occupy Overgaden’s ground floor galleries. The semi-transparent screen-prints making up Mette Winckelmann’s installation Come Undone create a theatrical front- and back stage inviting the viewer to encounter the space and the paintings from several positions. The installation both opens up and shuts out the viewer in relation to the works on view, proposing the viewer to navigate through it and encounter the paintings from different perspectives. The paintings and fields of colours within each one overlap and connect to each other creating a seemingly irregular yet structured system and abstract pattern.

Even though print making may evoke a turn in Mette Winckelmann’s practice which is perhaps more related to painting as such, it is a direction that comes quite natural. Fabric, patchwork, and print making have long been integrated material and techniques in the artist’s conceptual painting practice, and she also refers to these new works as paintings, or more precisely – a painting installation. If being already familiar with Winckelmann’s artistic work, one would recognise the artist’s use of an abstract, formal expression and language, which develops into something much wider and much more complex than just the colours and patterns represented on the fabrics and canvases. Yet, with Come Undone, I argue that Winckelmann has drawn her artistic expression even further into the field of minimalism and repetition, restricting herself in the working method, use of colours, materials, and dimensions of the works. There is also something deliberately unfinished and vulnerable in these new paintings on view. The artist has let go of her control, stopped the work before she thought or knew it was supposed to be finished. The contrast of this in relation to the use of mathematics and calculations to sketch out the patterns on the fabric creates a dynamic quality in the works, pointing towards a dichotomy (or maybe a hierarchy) between working methods, tradition, and individuality. To me, the use of a mathematic system could be seen as both a method of restrain as well as one of liberation where an act of letting go of control correlates with an indeed controlled method. The many paintings in the installation show almost a never-ending process, developed and thought-out in the same moment as it takes place, creating a flow in the space, putting us in doubt in regard to what we encounter and see.

The works are all screen-prints, printed on the type of unbleached cotton fabric often used by fashion designers in their preparation work trying out new designs and ideas, before making the final clothes in its actual chosen fabric. By using this type of fabric, an untreated natural product, as the canvas, Winckelmann explicitly points towards the process – the working situation – involved in the making of the paintings. The fabric, and the visible notes and pencil marks left on them, present the viewer with an insight into the artistic process and decision making. By close investigation one gets an understanding of the patterns and calculations the artist uses as a foundation for the works, before the actual application of colour is made. This conscious choice also opens up the question of what we really meet in the installation – is it completed works or is it sketches? Further, by not installing the works traditionally on the wall, but instead letting them hang from the ceiling in the gallery space, making the back and the frame visible for the viewer, the sense of being in the process-making is strengthened. The continued dialogue and exchange seem to take place, not only between the work and the viewer, but also between the work and the artist.

Apart from the neutral fabric selected as a ground, the paintings are made up of additionally four colours: white, red, black, and blue. The blue colour was added at a later stage in the process, signaling a different, yet co-existing time, and referring to the development of dyeing fabric where black, white, and brown nuances were for a long time the only colours on clothing. It is also said that ancient languages did not have a word for blue, thus raising the philosophical question whether blue as a colour even existed before it entered the modern vocabulary. Here, by adding blue, the reference to how we relate to ourselves and our collective history as a circular narrative and fluid organism becomes clear.

In the production of the paintings that compose the installation, two professional assistants have applied the colours by silk-screen technique. At the same time, the application of colours, all individual, reveals a similarity to the painter’s brush stroke as well as to a more mechanical industrial working process. The frames that are used for applying the paint all leave their individual traces and marks on the fabric, almost lending an imperfect result. This becomes even more evident, when the frames reveal that they have previously been used for other work, leaving not only paint but also visible patterns on the neutral fabrics. The overlapping of colour fields creates different nuances of the few colours used and also affects the transparency. And within this, together with the selection of colours used, I see a crucial aspect of the installation. It is an installation on work and labour, on revolution, on the individual in relation to the community. The reduction in patterns and colours may signify the repetition and monotonous act in the systematic working process we know since the industrial revolution. And given the specific inclusion of the colours red and black, not seldom associated with revolution, together with the tradition of craftsmanship in Winckelmann’s new work, lead the thoughts to the invention of the multi-spindle spinning frame “Spinning Jenny”, in 1764. This invention led to protests from hand weavers afraid of seeing their work being handed over to a machine. In an abstract and subtle way, Winckelmann’s painting installation points to this time in history not the least by revealing the craftsmanship behind her work. The installation pays tribute to a workers' tradition where the individuality reacts both against and in relation to the collective. In this perspective the relationship between weaving and text is also worth mentioning. Winckelmann stresses the communicative aspect of weaving by linking it to writing a text – the thread is the text, and textile and text originate from the same Latin texere. Throughout history we have also seen how textiles have been used for both describing and exchanging cultures, and later it has moreover been argued how female perspectives – both personal and political – have gained recognition through textile history.

Regarding the title Come Undone, this is not the first time Mette Winckelmann uses a song title as a title for one of her works. For example, previous works bear titles as Push It and Let’s Talk About Sex, both titles also used by the American hip hop trio Salt-N-Pepa. Come Undone could have many sources, both the British pop-band Duran Duran and British pop-singer Robbie Williams have made songs using the same title. But also the Canadian electronic musician and performance artist Peaches, though with a more sexual referring, spelled Cum Undun. Given Winckelmann’s interest and concern with gender issues, evident in her work for a long time, I understand the title as a comment to something falling apart, possibly hierarchies and systems. However the phrase is also used in the context of clothing not holding together, which also naturally relates to Winckelmann’s new installation. The artist has previously stated in response to her working method and choice of technique:

"Patchwork represents for me an alternative to mathematical and logical thinking, as a system which is organically subject to the individual person’s body and hand. The process of breaking a material up and placing it against another is interesting, because it’s exactly this rethinking of a given material which is in turn an image of our own body. A rethinking of the material can release the individual, and the individual body, from the way it is usually perceived."

Combining all of the above in approaching Mette Winckelmann’s installation Come Undone, the words “to enter a body” come to mind. It is an irregular, yet systematic formation, constructed of layer upon layer of known and unknown, of transparency and closure, of collectiveness and individuality, of tradition and revolution. The installation, in its inclusion of fragile materials and unfinished structure, presents us with vulnerability and mortality, telling us so much more than what we might see at first. It is a body which simultaneously teaches, gives hope and poses questions.

Andreas Nilsson is Assistant Curator at Moderna Museet Malmö.