The Craftswoman, 2013

Sally O’Reilly

Craft has had its ups and downs when it comes to its perceived status in the visual arts. For a whole generation, and not so long ago at that, it was discounted as conservative or lightweight; and yet artists like Mette Winkelmann use traditional craft techniques in progressive practices with serious aims. Quite how this transition has occurred is difficult to pinpoint, since fashions and fads are as prevalent and irrational in art as any other endeavour, but it could be precisely because of the previous ‘problems’ associated with craft that it is now employed as a critical tool, its common misconceptions giving it its teeth.

If craft were a character in a Hollywood film, she would be a handsome, full-skirted, upright woman of average means and admirable accomplishments, who makes small sacrifices to improve the lot of others. Championing over adversity, she would remain constant and true despite the misfortunes visited upon her by a capricious society. She would eventually marry well, and romantically, and her husband would spot the potential of her exquisite crafts practice. He would encourage her to mechanise and expand, until eventually our heroine became the primary manufacturer of an excellent product in a region where the landscape is rugged and the people honest.

This may be a somewhat facetious caricature, but it relates many an extant attitude to craft: that it is allied with tradition and in opposition to industry; that it is modest, ethical and authentic, in essence practical but intensely aestheticised and, perhaps above all, that it is distinctly gendered. The feminine associations of craft are partly due to its decorative status, and partly to do with the belief, as a consequence of The Fall perhaps, that since leisure leads to temptation, a woman’s hands must be kept busy at all times. Freud cast woman as weaver and knitter on account of her tangled pubis, and indeed it is only comparatively recently that many school curriculums have identified craft lessons as unisex. But this genderisation runs counter to the authority held by the crafts guilds in medieval European cities, as well as its role in the formulation of mass production and such industries as computing. In fact, if we think historically, craft cannot really be considered in opposition to commercial production at all.

The Classical Greek term Techne – from which technology, the vehicle of industry, etymologically springs – refers to the attainment of understanding through doing, and was deemed inferior to philosophical, abstract knowledge. In recent decades an equivalent of this attitude could be discerned among the many neo-conceptualists who rejected conventional skills and virtuoso techniques in favour of radical deskilling or dematerialisation.

Between these two historical points, though, the industrial revolution has precipitated major transformations of societies and individuals, so the comparison is much less straightforward than it at first appears. Without resorting to an over-simplified historical account, it is suffice to say that one of the prominent effects of this protracted revolution was the displacement of the human hand by the machine. But the important point to note here is that techne is to do with making and performing, as opposed to hypothesising, and whether this is aided by technology or not is by the by. Craft is another form of techne, in that it is hands-on and produces a body of knowledge about and for a community. What is more, we can think of any tool that extends the natural capacities of the unaided human body as a technological prosthesis: the cup is a better version of our hands, spectacles a sharpener or straightener of the eye’s own lens, the car is faster and has more stamina than our own legs. And similarly, a needle is a sharp and independently articulate finger, cloth is a skin, a loom is the equivalent of many tireless hands. Furthermore, if we take manus – the Latin for hand, which gives us such words as manipulate, manager, manacle and mandate – we start to understand the authority we afford to acts of the hand, despite their apparent demotion in the post-industrial era. Indeed, the roots of our everyday language suggest that craft and industry have not quite separated in our imagination.

It is undeniable, however, that the industrial revolution precipitated a vast extension of our bodily capacities that must be traumatising at an atavistic level. The evolutionary biologist John Maynard Smith proposed a disturbing illustration of this when he imagined a two-hour film relating the evolution of tool-making man: the domestication of animals and plants would be shown only during the last half minute, and the period between the invention of the steam engine and the discovery of atomic energy would be only one second. The vast majority of the film would relate the localised application of tools to materials held in the hand – singular work for immediate use. The later phase of rapid extension of our reach is pretty alarming, and in this light Winkelmann’s employment of craft might be thought of as recuperative. Her handmade images and objects, while obviously artworks, recall artisanal counterpanes, wall hangings, rugs, murals and mosaics; and this resurrection of the beautifying facility of the arts and crafts of bygone eras, following a century of the denial of high art’s decorative and socialising potential, reintroduces the body as fabricator and appreciator of such crafted objects.

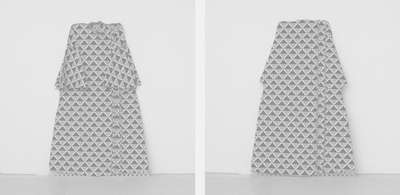

When art has been claimed to be radicalising, progressive or new, it has often actively and openly rejected conventions and precursors. Much of the development of the modernist movements is down to this patricidal impulse, but it seems unnecessarily destructive today, when what has gone before can be rescripted, remodelled and reapplied to new ends. Conventions are ironised or adopted uninflected by the contemporary artist to express new thoughts in new contexts, as does Winkelmann when she presses histories of painting and quilt making into new material encounters that challenge normative narratives of the body in society. The ethos of North America quilt-making collectives, for instance, was co-opted by civil-rights and feminist movements to signify defiant cooperative action and the potential for radical change through incremental shifts. The Scandinavian model, meanwhile, is more insular, although still socialising, with practitioners working on their own pieces, but swapping fabric by way of social networks. And the African American women of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, produce improvised designs that dissolve the rigidity of the grid, their warped bars and panels eliciting a charm that bears a strong relation to the orientalism and primitivism of the European avant-garde. Winklemann calls on all these, and other, vernaculars, admiring the perpetuation of each tradition and its evolution through individual interpretation, which she then pushes even further to address to her own social, physical, intellectual and emotional contexts. Works like Finished, Unfinished, Crossed (2012), which brings together Swedish cross-stitch and references to the Navajo tradition, articulate the sense of embeddness and dislocation many feel, even in the societies they are born into, while The Four Parts (2013) channels the autobiographical through old curtain material and batik fabric made by the artist’s sister when she was a teenager. More politically direct, 30,000,000 lesbians (2009) comprises fabric from two of her mother’s skirt-making kits, some chinoiserie and a repeating print with a stylised fire motif. The title challenges the official assertion that there are no lesbians in China – applying averages elsewhere to the country’s population – and the assumption in most Western societies that homosexuality is predominantly male. The object itself, then, becomes a flag for visibility, a demand for women of all backgrounds to stand up and out and be counted.

Throghout Winkelmann’s practice the political message is woven through the form of the work itself. The mutability demonstrated by sewn fabric collages such as Column of Constellations (2011), and its translation into a painted counterpart, create a déjà-vu experience: the repeated glimpse of a shape, colour or pattern becomes an allegory for the ultimate reconfigurability of people and situations. The grid, when wrought from fabric, is so different to that made in paint that it demonstrates how materiality produces certain effects, but that we are free, to an extent, to choose the nature of the materials we apply our efforts to. Winkelmann talks of how the majority of a society adhere to received formats for societies, families and households, but these are by no means set. While such conventions have grown from certain biological imperatives, these can be culturally overruled. Rather than a fixed template, society should be an openwork in progress. To reflect these aspirations, Winkelmann’s riffs on composition, pattern and rhythm, throughout her two- and three-dimensional works, generate an atmosphere of collective storytelling, where themes and motifs recur again and again in perpetually new variations. And the more we retell these stories, the more we strengthen the sense that we are all cut from any combination of familiar, tradable cloths, that there are innumerable new ways of arranging matters.

As an instance of this transformability, the bathroom at Kunstmuseet Brundlund Slot will be revamped using a similar technique to the collaged commercial flooring to Used in Denmark (2011), a triangular podium with under-floor heating, which invited gallery visitors to splay out across its surface. At the Slot the surface of the bathroom interior will splinter improbably, the contingencies of the bathroom, usually dictated by the demands placed upon it by the functions of the body, will be reorganised into an encounter intended to indulge the senses of those very bodies. It is this drift of craft into aesthetics and away from the results-driven world of commercial design, an organic hand-to-hand development based on necessity and caprice rather than accuracy and accrual, that brings it further into line with the political intention of many artists – namely, the eschewal of efficient utility. At a time when an object can be precisely reproduced by a three-dimensional scanner, pretty much at the press of a button, the repetitive crafting act might seem absurd to some. But although machines also perform repeated actions – at many, many times the speed of the human hand – it is at a constant frequency with uniform results. The idiosyncrasies and nuances of the individual body and mind are regulated by mechanics and electronics, and the gradual emergence of a hand-hewn object is replaced by unambiguous instantaneousness. But perhaps we value the crafted object not because of the time put into its facture – time as money, literally – but because we imagine we are being specifically addressed through it. Hands, as the tool of tools, the articulated interface between self and world, simultaneously project us out into our surroundings and draw the exterior towards us; and crafting hands perform a meta operation by generating objects that remind us of this intersubjectivity. The one-off object speaks of a particular event in a certain time and place, fixing in material what would otherwise be lost to the flood of history.

But Winkelmann is not unconditionally elevating craft. She uses machine-made fabrics, commercial floor tiles and regular building materials, such as milled wood and mass-produced bricks. Hers is not a utopian practice, but a thoughtful consideration of the vacillating status of the made and the bought. The invertible cups in Pattern of the Day (2011), for instance, were made by a potter and are distinctly reproducible, but the perverse way in which they offer then scupper their for potential dual-use animates the shifty threshold between innovation in business and absurdity in art. Throughout the industrial era the singular, hand-hewn object has been valorised by the high-end markets, but then it is the wide-spread desire for the mass-produced that keeps economies afloat. Handicrafts have a charm that appeals, and it is the flaws of handmadeness that are often considered the mark of precious individuality and are ultimately collectible. But then craft is also looked down upon as therapeutic or irrelevant to our times, and many favour the perfection of a mass-produced object that does not bear traces of the human hand. The slickly manufactured object enacts a classical instance of poesis – that is, the sudden arrival of something where before there was nothing. It can provoke wonderment. We used to require this brand of genius from our artists, but these days we perhaps prefer to see the artist’s struggle with matter. We like to empathise with hard-won mastery over materiality.

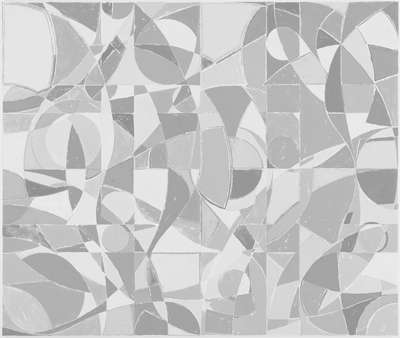

Winkelmann considers the relation between the rational and the sensual with similar equivocation. The means by which she arrives at a design often has the appearance of logic, particularly geometry and architectonics; but for her geometric space is somewhere to park the body and to exert the messier aspects of human influence. She reclaims abstraction from its masculine past, signalling not inscrutable progress towards perfection, but the multi-directionality, and ultimate fallibility, of thought. Her geometric compositions are by no means hard edged – their shimmer is that of the embodied, dancing line, not the cerebrally projected. And she often shows the workings of her thinking, drafting and making processes, so that we might reflect on their aims and influences. But just as the human brain is often a jumble of thoughts, these workings are scattered with red herrings and cul-de-sacs, and we can never quite retrieve the formula or recipe for a work. Just as storytelling is a way of tidying up life so that we can pass it on without its falling back into the chaos of experience, Winkelmann’s flags, banners, paintings, pedestals, clusters and constellations too are contingent compositions for carrying complex impulses and ambitions. The aim, though, is not that we necessarily reconstitute these complexities with accuracy, but that we can sense the convolutions they embody.